By Kara Nyberg, PhD

Posted: August 19, 2020

A multitude of factors contribute to disparities in lung cancer care, including sex, race, education level, income, geographic region, and access to care. “There are some systemic barriers that make it difficult for people to obtain equitable treatment by race and class in the United States,” regardless of the type of disease, according to Christopher Lathan, MD, MPH, Medical Director of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute at St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center and Faculty Director for Cancer Care Equity. These disparities are exacerbated in lung cancer because socioeconomic status and race represent major determinants of smoking, the leading cause of the disease.

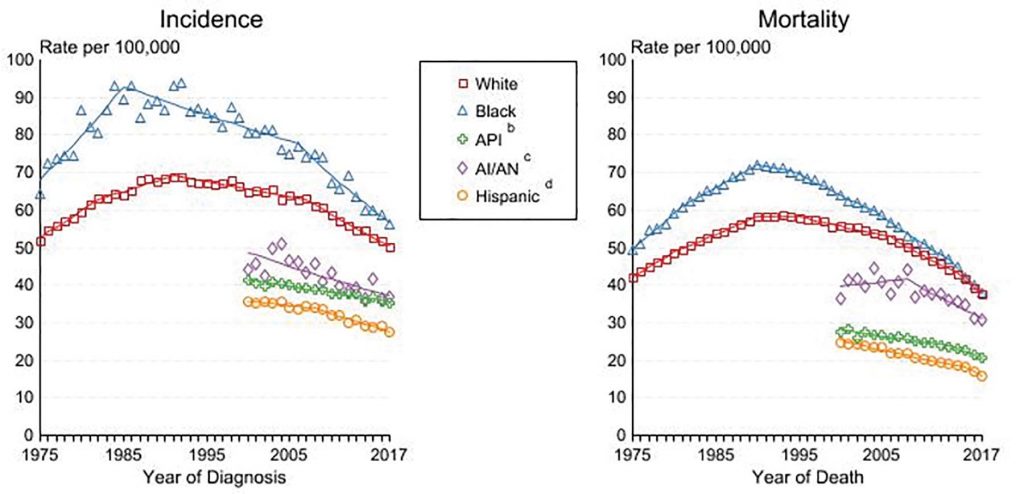

Although change has been slow, improvements in lung cancer disparities are beginning to emerge on several levels, particularly over the last 5 years. If we look at race, the most conspicuous and topical disparity based on recent events worldwide, lung cancer incidence and mortality have continued to steadily decline in the United States across all races, with diminishing gaps between white and black individuals (Figure 1).

a Rates are age-adjusted to the 2000 US Std Population (19 age groups – Census P25-1103).

Regression lines are calculated using the Joinpoint Regression Program Version 4.8, April 2020, National Cancer Institute. Joinpoint analyses for white and black individuals during the 1975-2017 period allow a maximum of 5 joinpoints. Analysis for other ethnic groups during the period 1975-2017 allows a maximum of 3 joinpoints.

b API = Asian/Pacific Islander.

c AI/AN = American Indian/Alaska Native. Rates for American Indian/Alaska Native are based on the Purchased/Referred Care Delivery Area (PRCDA) counties.

d Hispanic is not mutually exclusive from whites, blacks, Asian/Pacific Islanders, and American Indians/Alaska Natives. Incidence data for Hispanics are based on NHIA and exclude cases from the Alaska Native Registry.

Source: Incidence data for white and black individuals are from the SEER 9 areas (San Francisco, Connecticut, Detroit, Hawaii, Iowa, New Mexico, Seattle, Utah, Atlanta). Incidence data for Asian/Pacific Islanders, American Natives, and Hispanics are from the SEER 21 areas (SEER 9 areas, San Jose-Monterey, Los Angeles, Alaska Native Registry, Rural Georgia, California excluding SF/SJM/LA, Kentucky, Louisiana, New Jersey, Georgia excluding ATL/RG, Idaho, New York, and Massachusetts).

Still, many disparities in lung cancer burden persist across multiple segments of the population, which makes it important to understand the past trajectory of these inequities and how to sustain positive trends moving forward.

Addressing Screening Disparities

The greatest advancements in lung cancer screening over the past decade involved recognition of the impact of screening, followed by screening reimbursement. In 2011, the National Lung Screening Trial showed that screening high-risk individuals annually with low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) reduced lung cancer deaths by 20%.1 Not long thereafter in 2014, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) endorsed LDCT screening for high-risk individuals, ensuring coverage by commercial health insurance companies under the Affordable Care Act.2 The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) followed suit in 2015, guaranteeing insurance coverage for LDCT screening for all eligible Medicare beneficiaries.3

“Since 2015 when the CMS national coverage determination came out, there’s been a slow but steady increase in the number of facilities offering screening and the number of patients receiving screening. It’s still inadequate and far too low. But just the fact that screening is there and that, with very few exceptions, individuals who meet eligibility criteria can be screened with no copay or cost-sharing is really significant,” said Angela Criswell, MA, associate director of Quality Screening & Program Initiatives for the GO2 Foundation for Lung Cancer.

The GO2 Foundation has been a driving force in promoting equitable access to lung cancer screening in the United States. In 2012, the nonprofit organization launched the National Framework for Excellence in Lung Cancer Screening and Continuum of Care that now includes a network of more than 700 Screening Centers of Excellence across the United States devoted to lung cancer screening for high-risk individuals, about 60% of which are located in community settings.

A 2016 survey of 165 of these Screening Centers of Excellence revealed that stage I NSCLC represented 49% of all lung cancer diagnoses made at the community and academic sites.4 Considering that only 26% of all NSCLC diagnoses were stage I according to a 2010 analysis of the National Cancer Database,5 the results suggest that community centers, along with academic sites, off er a powerful resource for shifting the trajectory of lung cancer outcomes through earlier diagnosis.

Still, even with the advances achieved by the GO2 Foundation Screening Centers of Excellence Network, disparities exist. “We work really hard to have broad geographic representation, but screening is still predominantly centered in urban areas,” Ms. Criswell said. Many of the screening centers have also found that the individuals coming in for screening are of higher socioeconomic status.

To better close these gaps, the GO2 Foundation is piloting the Alabama Lung Cancer Awareness, Screening, and Education (ALCASE) project, a grassroots effort conducted in collaboration with the University of Alabama at Birmingham’s O’Neal Comprehensive Cancer Center and led by Project Manager Kathy Levy. ALCASE targets several rural, underserved counties in Alabama featuring predominantly black populations with high smoking rates. The program utilizes community health advisors—individuals viewed as trusted leaders within the community—to raise awareness about lung cancer risk and screening. ALCASE staff have also worked to expand the network of Screening Centers of Excellence regionally to reduce the distance individuals need to travel for LDCT screening.

“Even though we now have a platform of low-dose CT to detect early-stage lung cancer, we still have a ton of work to do,” commented Mary Pasquinelli, DPN, APRN, director of the Lung Cancer Screening Program at the University of Illinois Hospital and Health Science System.

Most notably, the current USPSTF eligibility criteria for screening do not adequately reflect the risk for lung cancer among black individuals, who show the highest rates of developing and dying from lung cancer, and who do so at younger ages and despite smoking fewer cigarettes per day compared with white smokers. The National Lung Screening Trial data on which the USPSTF screening recommendations are based define high-risk individuals as people aged 55 to 74 years who have at least a 30-pack-year smoking history and who, if former smokers, had quit within the previous 15 years. However, Dr. Pasquinelli noted that the National Lung Screening Trial included 91% white individuals and only 4.5% black individuals, resulting in data that do not sufficiently represent minority-based populations, particularly with regard to age and smoking burden.

Translating disparate data into preventative strategies could paradoxically increase racial disparities in lung cancer outcomes, according to Dr. Pasquinelli. A recent analysis of lung cancer cases diagnosed between 2002 and 2014 showed that black individuals were less likely to be eligible for lung cancer screening compared with white individuals when applying the USPSTF eligibility criteria— a finding that held true even among the individuals actually diagnosed with lung cancer during the study.6

“As the research evolves, we have to keep changing our game plan by looking at the evidence, looking at health inequities, and trying to improve upon health outcomes,” Dr. Pasquinelli remarked.

Addressing Treatment Disparities

Of course, many of the disparities that pertain to screening carry over to treatment as well—for example, disparate care provided at community hospitals versus academic centers. “A lot of the advances haven’t disseminated well into the community. There are data that comprehensive biomarker testing is not always happening, and even if the tests are ordered, doctors aren’t always following through on the results,” according to Jennifer C. King, PhD, chief scientific officer at the GO2 Foundation. “We know how to treat patients more effectively than we did a decade ago, but not everybody is getting that level of care.”

Researchers are beginning to devise strategies that show promise for eliminating inequities in treatment. For example, to address race-associated treatment disparities in patients with early-stage lung cancer, Samuel Cykert, MD, and colleagues conducted a 5-year clinical study that utilized alerts linked to electronic health records signaling missed appointments or care milestones, a nurse navigator who followed through on the alerts, and race-specific feedback to clinical teams on treatment completion rates. The multifaceted intervention not only reduced treatment gaps between black and white patients with stage I/II NSCLC, but it led to better care for all individuals.7 Before the intervention, 69% of black patients and 78% of white patients received potentially curative treatment with surgical resection or stereotactic radiation based on retrospective data; however, after the intervention, treatment rates reached 95% or greater for both races.

The Future

“You can’t take away systemic barriers and systemic oppression with one intervention, but we can try,” says Dr. Lathan. Toward that end, Dr. Lathan is encouraged by the role that patient navigators can play in equitable access to treatment. “We know that navigation can help mitigate disparities. In theory, what the navigator is trying to do is circumvent the structural barriers that are in place,” he said.

Dr. Lathan also thinks that clinicians need to be more mindful of their own internal biases regarding smokers and make more of an effort to invest the necessary time and resources to help individuals quit smoking—a strategy that can reduce lung cancer burden and ultimately save lives. “Investment in this type of prevention can be very helpful. It just needs to be targeted to communities and done in a way that is respectful of the community,” Dr. Lathan said.

“I think we’re all more aware of disparities,” Dr. Pasquinelli remarked. To now rise to the occasion, “we need to be sure that we’re meeting every patient with the best standard of care that we can possibly give them, no matter what hospital they go to, no matter where they come from, no matter their education level.” ✦

References:

1. Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(5):395-409.

2. Moyer VA; US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for lung cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(5):330-338.

3. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services: Decision memo for screening for lung cancer with low dose computed tomography (LDCT) (CAG-00439N). https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-decision-memo.aspx?NCAId=274

4. Copeland A, Criswell A, Ciupek A, King JC. Effectiveness of lung cancer screening implementation in the community setting in the United States. J Oncol Pract. 2019;15(7):e607- e615.

5. Morgensztern D, Ng SH, Gao F, et al. Trends in stage distribution for patients with non-small cell lung cancer: A National Cancer Database survey. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:29-33.

6. Aldrich MC, Mercaldo SF, Sandler KL, Blot WJ, Grogan EL, Blume JD. Evaluation of USPSTF lung cancer screening guidelines among African American adult smokers. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(9):1318-1324.

7. Cykert S, Eng E, Walker P, et al. A system-based intervention to reduce Black-White disparities in the treatment of early stage lung cancer: A pragmatic trial at five cancer centers. Cancer Med. 2019;8(3):1095-1102.