Posted: August 14, 2019

Mark A. Socinski, MD, executive medical director of AdventHealth Cancer Institute, spoke with the IASLC Lung Cancer News about his personal recommendations for TKI-refractory disease, especially for patients with EGFR mutations. He discussed the latest IMpower150 data,1 as well as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA’s) decision not to approve this regimen for patients with EGFR/ALK mutations. Dr. Socinski also shared his thoughts on the use of bevacizumab and toxicities related to a four-drug regimen.

Q: How do you typically treat patients with oncogenic drivers and TKIrefractory disease?

A: Let’s start with the basics. Every patient, particularly those with adenocarcinoma, should be comprehensively tested for oncogenic drivers. The current National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommendations call out the big four: EGFR, ALK, ROS-1, and BRAF, but there are others such as MET, RET, and HER2. I endorse comprehensive testing for oncogenic drivers because I think that we have repeatedly seen that if an oncogenic driver is identified and the patient receives an effective targeted agent, typically a TKI, the progression-free survival (PFS) and the response rate are so much better when compared with standard chemotherapy. This is typically not a group of patients that has as “big of a bang” with immunotherapies, so all TKI options should be exhausted before considering other agents.

Specifically regarding EGFR, the standard of care is osimertinib in the first-line setting. We do not understand as much as we would like about why patients become refractory to osimertinib, so most of those patients, particularly in routine practice, are going to move to standard chemotherapy after disease progression. These patients almost always have adenocarcinoma, and most of these patients have good performance statuses and are chemotherapy naive; for these reasons, I typically treat with a platinum-based chemotherapy doublet. I typically use carboplatin, although cisplatin would be fine. I pair it most typically with pemetrexed, although paclitaxel is an option.

Q: Do angiogenesis inhibitors have a role in this setting?

A: I believe that antiangiogenic therapy does have a role in this setting, but I will also say that not every patient is a preferred candidate for a drug like bevacizumab. In fact, administration of an antiangiogenic therapy is only appropriate in approximately 30% to 50% of patients with oncogenic drivers. If the patient is a candidate, however, I consider adding bevacizumab to the chemotherapy doublet. Depending on patient preferences regarding side effects, I will use either pemetrexed or paclitaxel. The POINTBREAK trial taught us that whether pemetrexed or paclitaxel is used, the overall survival (OS) and response rates are the same.2 There was a statistically significant but not clinically meaningful difference in PFS in the trial, so I think that you could use either carboplatin and pemetrexed plus bevacizumab or carboplatin and paclitaxel plus bevacizumab; the latter is the ECOG4599 regimen.3

Q: The FDA recently failed to approve the IMpower150 regimen for patients with TKI-refractory disease with EGFR/ ALK mutations. Was this a mistake?

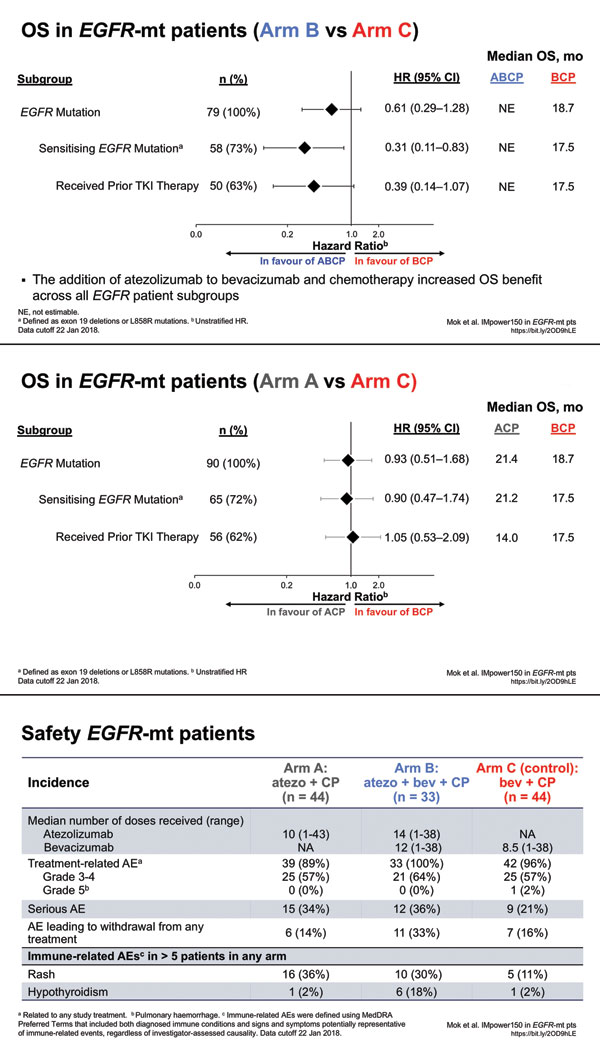

A: IMpower150 was performed because preclinical data suggested that the combination of a vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibitor with a PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor could have added synergistic effects regarding manipulation of the immune environment. For example, high VEGF states are known to be immunosuppressive in a number of different ways. If you inhibit both VEGF and PD-1/PD-L1, there might be a greater benefit, which was what IMpower150 showed, with four drugs proving superior to three drugs for the intent-to-treat population. In my mind, this validates the concept of adding immunotherapy to anti-VEGF therapy. There are a few settings in which VEGF may be a bit more involved in the pathogenesis of the disease, such as patients with EGFR mutations or with liver metastases. Those are the two subsets that we opted to study, and both showed positive effects for the addition of anti–PD-L1 therapy to anti-VEGF therapy. A substitution strategy using anti–PD-L1 for anti-VEGF therapy in Arm A resulted in no significant difference—maybe a trend, but not like what was seen with the additive effect.

Patients with EGFR/ALK mutations have been excluded from enrollment in every trial presented to date, with the exception of IMpower150 and IMpower130, which assumed that patients had received prior TKI therapy if appropriate. (Not every patient with an EGFR mutation has a sensitizing mutation, so there are patients with EGFR mutations for whom TKI therapy was not appropriate.) Going into IMpower150, we had no way to know how many patients would end up on the trial. Regarding patients with EGFR mutations, there were ultimately 45 on Arm A, 34 on Arm B, and 45 on Arm C. Although the study regimen included this population, the FDA was not sold on the benefit for the EGFR-mutation population because of the small numbers. I have been told that there were no other issues preventing approval for this group other than the inability to have prospectively powered the trial specifically for patients with EGFR mutations, which was not possible because we did not know beforehand how many patients with EGFR or ALK mutations would end up on the trial and how many of those patients had “failed” prior TKI therapy.

Regarding IMpower150 OS data presented at the European Society for Medical Oncology in November 2018, the hazard ratio for OS for patients with EGFR-sensitizing mutations was 0.31 for the addition of atezolizumab to the ECOG4599 regimen, which is pretty convincing. Similarly, the hazard ratio for patients with EGFR mutations who had received a prior TKI was 0.39. So in my mind, these hazard ratios are impressive despite the small population of patients with EGFR mutations in this trial.

Q: Does toxicity preempt the use of a four-drug regimen?

A: Patient selection is key. If you take all-comers with nonsquamous NSCLC, then 60% to 70% of patients would have a contraindication to bevacizumab. These patients often have untreated brain metastases, comorbidities, recent myocardial infarctions, history of stroke, and/or hypertension that’s difficult to control. However, if a patient is a perfect candidate for bevacizumab, POINT-BREAK showed acceptable toxicities for the addition of bevacizumab to carboplatin and paclitaxel or carboplatin and pemetrexed. In my experience, adding immunotherapy to chemotherapy doesn’t exacerbate the toxicities of either modality. However, because more therapy is being given, there is going to be the risk of more toxicity. Physicians must talk to patients about the advantages and risks of being more aggressive with therapy. You have to listen to patients about preferences. Some patients will want to do whatever it takes to stabilize or shrink their disease; other patients feel differently. I personally do not think the four-drug regimen is prohibitive with regard to toxicity. Four-drug regimens have been administered before in different settings, even in settings where the four drugs did not help. Here we have a situation in which a four-drug regimen seems to help—quite significantly for patients with EGFR mutations, which is, I think, the only oncogenic driver that we can talk about somewhat confidently. The ALK population in IMpower150 was too small, and we do not have data regarding other drivers such as BRAF and MET. I think many people might draw conclusions about these other drivers, but these conclusions would not be data-driven.

Q: Do you continue the TKI during chemotherapy if the patient has been shown to have TKI-refractory disease?

A: When the decision is made that the TKI has worn out its welcome and it is time to move on to chemotherapy— whether it is chemotherapy alone or chemotherapy with bevacizumab or the IMpower150 regimen—then I stop the TKI. Based on the IMPRESS data and other trials, I do not believe that keeping the TKI has a benefit.4 Again, the more drugs you have, the higher the risk of toxicity. Although it might be safe, I am not sure that I am providing a greater benefit by continuing the TKI. There is room for discussion, however, about whether the TKI could or should be done as maintenance therapy as part of the initial post-TKI regimen. ✦

References:

1. Socinski MA, Jotte RM, Cappuzzo F, et al. Atezolizumab for First-Line Treatment of Metastatic Nonsquamous NSCLC. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(24):2288-2301.

2. Patel JD, Socinski MA, Garon EB, et al. PointBreak: a randomized phase III study of pemetrexed plus carboplatin and bevacizumab followed by maintenance pemetrexed and bevacizumab versus paclitaxel plus carboplatin and bevacizumab followed by maintenance bevacizumab in patients with stage IIIB or IV nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(34):4349-4357.

3. Sandler A, Gray R, Perry MC. Paclitaxel-carboplatin alone or with bevacizumab for non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(24):2542-2550.

4. Mok TSK, Kim SW, Wu YL, et al. Gefitinib Plus Chemotherapy Versus Chemotherapy in Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Mutation- Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Resistant to First-Line Gefitinib (IMPRESS): Overall Survival and Biomarker Analyses15. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(36):4027-4034.