By Linda Coate, MD, FRCPI, and Hazel O’Sullivan, MB, Bch, BAO, MRCPI

Posted: August 14, 2019

The Republic of Ireland has a publicly funded healthcare system, financed by general taxation.1 Approximately 43% of the population also has private health insurance.2 Approximately 35% of patients have a “medical card,”3 which entitles them to free hospital attendances, general practitioner visits, and heavily discounted medications. Many citizens have both means to access healthcare. All Irish citizens aged 70 and older are entitled to a modified medical card but may have to pay for medication, and patients younger than age 70 are means tested following their medical card requests. All citizens are allowed to apply for a drug subsidy scheme, which caps payments to community pharmacies (including a number of high-cost oncology drugs taken orally and dispensed monthly). Drug costs for patients undergoing cancer treatment in a private hospital are borne by the patients’ insurance company. Drug acquisition costs, but not cost of care, are borne by the government system for patients with insurance being treated in a public hospital. This complex, overlapping, and often confusing landscape of public and private medicine in Ireland makes an already intricate and often emotive pharmacoeconomic area in medicine difficult to examine and measure, even within—or perhaps particularly within— the presumed healthcare homogeneity of the European Union (EU).

Relation Between Regulatory Approval, Treatment Cost

Ireland is a member of the EU, and, therefore, medicines in Ireland are subject to regulatory approval as a member state. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) is responsible for the scientific evaluation, supervision, and safety monitoring of all medicines in Europe.4 Cancer medicines must be approved by the EMA prior to pharmaceutical companies’ application for market authorization in Ireland. Following the application, the National Centre for Pharmacoeconomics (NCPE) is the government agency responsible for decisions regarding the reimbursement of new cancer drugs. The NCPE considers the therapeutic benefit of the agent, its cost-effectiveness, and budgetary effects. The NCPE will carry out a “rapid review” of the application within 4 weeks (in practice, this can take much longer). If it is felt a full economic evaluation is required, a health technology assessment will be performed within 90 days (delays at this point are also possible). Once a positive recommendation has been made by the NCPE, the result is returned, and a national chemotherapy protocol is written. An Irish physician can prescribe a medicine not subsidized publicly once it has had EMA approval, but insurance companies usually fund the cost of the agent following the recommendations of the public system. Increasingly, demands for off-label use of cancer drugs have resulted in patients paying out of pocket for their cancer medications. This is also true for those medications that are licensed, but not yet reimbursed (the socalled “valley of death” in a memorable plenary session at the European Society for Medical Oncology 2016 Congress).

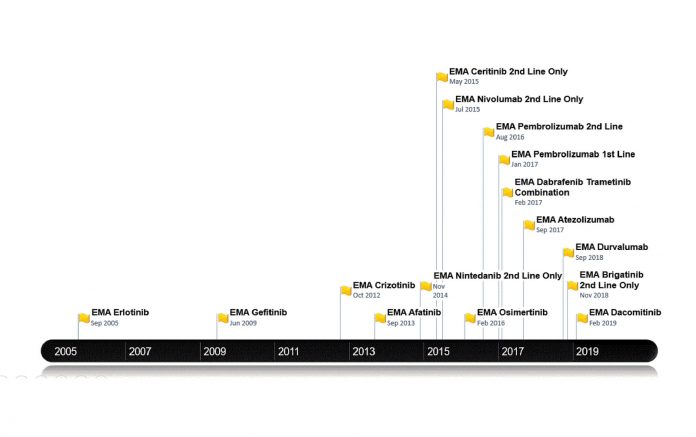

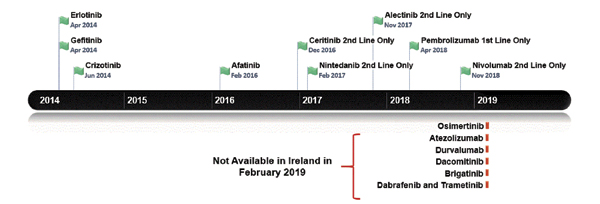

Figure 1 outlines the dates of the recent NSCLC treatments approved by the EMA. This generally temporally follows, but is broadly in line with U.S. Food and Drug Administration approvals. Figure 2 lists the treatments funded in Ireland along with reimbursement dates. Note that prior to April 2018, patients with lung cancer in Ireland did not have access to immune checkpoint inhibitors for any indication. Until the time of writing of this article, funding for immunotherapy was confined to those patients with PD-L1 expression of greater than 50%. Nivolumab is now available for treatment of patients in the second line; atezolizumab and durvalumab await reimbursement decisions.

Currently, patients with a T790M EGFR mutation cannot receive osimertinib unless they pay out of pocket for the drug achieved sometimes by crowdfunding. Astra Zeneca first applied to the NCPE for reimbursement in February 2016, but the company’s request was denied following a pharmoeconomic assessment. Further applications have been made but have been rejected, as it was deemed not cost effective. However, the drug is under reassessment.5 For patients with ALK-positive disease, there is publicly reimbursed access to crizotinib in the first-line setting and to both ceritinib and alectinib in the secondline setting. The disparity and inconsistency between regulatory approval and the decision to fund cancer medicines in Ireland has left a “vulnerability gap.” This gap means that the value of medicine at price-point purchase (sometimes because of hastily negotiated reimbursements bowing to political pressure) and more importantly patient well-being can suffer. The latter is often both literal and figurative with both an actual and perceived lack of access to treatment.

There is also variation in cost. “Listprice” cost is not reflected in actual cost negotiated by the public system or with insurance companies or private hospital groups. In the case of patients who pay for their own medications, certain agents are sometimes offered at a discounted rate when compared with the “list-price” value. This information is not readily available in the public domain.

Using Challenges to Spark Enthusiasm, Partnership

Because of these increasingly lengthy roads to insurance-funded treatment and the impressive scientific strides made within the field, enthusiasm for participation in lung cancer research studies has increased. Up until relatively recently, thoracic oncology patients in Ireland had no or limited access to novel therapeutics through clinical trial participation. During the past several years, significant effort has been expended into lung cancer clinical research programs in Ireland.

Established in 1996, Cancer Trials Ireland (CTI) is the leading clinical trials organization in Ireland, and with cooperation from industry, it has coordinated much of this effort. It provides a range of cancer trial functions including planning, opening, co-coordinating, supporting, monitoring, and auditing of trials to facilitate the important work of researchers in Ireland but also to extend involvement to other European countries. In this regard, CTI has often acted as a trial sponsor.

More recently, between 2014 and 2018, lung cancer trial accrual in Ireland has doubled from very humble beginnings. Treatment trials have recruited between 40 and 75 patients per year, with many more participating in translational research studies. This growth has been achieved despite the absence of direct investment and even a 20% budgetary cut to the funding of a cancer research infrastructure during this period in Ireland, and so our hope is that this fledging group will continue to grow. Patients, investigators, and research teams in Ireland have participated in some of the most highly cited and practice-changing industry-sponsored studies including KEYNOTE-024, KEYNOTE-189, CheckMate 227, and CheckMate 451. Collaborations with cooperative groups include European Thoracic Oncology Platform–sponsored trials such as BELIEF, EMPHASISlung, and SPLENDOUR, and patients in Ireland have also participated in the ECOG 1505 adjuvant study.

The lung cancer trials portfolio includes radiotherapy, translational, basket, and investigational medicinal product studies in both NSCLC and SCLC, ranging from local to advanced metastatic disease. These trials offer treatment options not otherwise available to thoracic oncology patients in Ireland through other channels, such as licensed treatments or compassionate-access programs.

As of January 2019, there were nine open lung cancer trials, an additional nine trials in the feasibility and set-up stages, and another 10 trials in the followup or close-out phases.

As researchers, physicians, care teams, and patient advocates working together for lung cancer care in Ireland, we are hopeful that drug access and equity of care for our patients will continue to improve, facilitated by our striving for clinical excellence through research.✦

Acknowledgments to Vincent O’Mahony (Project Manager Cancer Trials Ireland) and Dr. Hazel O’Sullivan (Specialist Registrar, ICHMT).

About the Author: Dr. Coate is a consultant medical oncologist and an assistant professor in Medicine at the University Hospital Limerick. She chairs the Lung Cancer Clinical Trials Group for Cancer Trials Ireland. You can follow her on Twitter @lindacoate. Dr. O’Sullivan is Medical Oncologist Specialist Registrar at Mater Misericordiae University Hospital, Dublin, Ireland.

References:

1 Health Service Executive. hse.ie. Accessed February 24, 2019.

2 Private Health Insurance. An Roinn Sláinte Department of Health. health.gov.ie/publications-research/statistics/statistics-by-topic/private-health-insurance. Accessed February 24, 2019.

3 Ireland’s Open Data Portal. Department of Public Expenditure and Reform. data.gov.ie. Accessed February 24, 2019.

4 European Medicines Agency. ema.europa.eu/ema. Accessed February 24, 2019.

5 Osimertinib (Tagrisso®). National Centre for Pharmoeconomics Ireland. cpe.ie/drugs/osimertinib-tagrisso. Accessed February 24, 2019.