By Pedro N. Aguiar Jr., MD, MSc, and

Gilberto L. Lopes Jr., MD, MBA

Posted: April 2018

After often-painful but effective and still incomplete economic reforms, more rational government spending, and the increased trade brought about by globalization, Latin America has lifted itself out of the misery of its recent past and has started to tackle its large but still appalling economic disparities. With development has come an epidemiologic transition, making chronic non-communicable diseases the most important cause of mortality in the region.1 Lung cancer incidence in Latin America is increasing, and approximately 70% of patients present with advanced disease2; estimates suggest there will be 541,000 new cases and 445,000 deaths due to lung cancer in Latin America by 2030.3

Latin American countries invest only $7 or $8 per patient with cancer, whereas the corresponding figures for the United Kingdom, Japan, and the United States are $183, $244, and $460, respectively.4

LUNG CANCER IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES

As a result, North America, Europe, and Japan consumed 88% of the new pharmaceutical products launched from 2005 to 2009, whereas the rest of the world was responsible for only 12% of expenditures in medications.5

The high cost of innovative therapies, such as targeted therapies and immune checkpoint inhibitors, is likely to make these numbers even more disparate in the future. In the United States, the average yearly cost of new drugs for patients with cancer often exceeds $100,000,6 which is obviously unaffordable in lower-income countries. In recent years, pharmaceutical companies have started to offer medications at lower prices outside of North America, Western Europe, and Japan. Economists call this “price discrimination”: when the cost of development of a service or product is significantly higher than the cost of producing extra units of the product, companies make more money and consumers have greater access to therapies if the company sells the product or service with different prices in different markets, based on the specific market’s ability to pay.

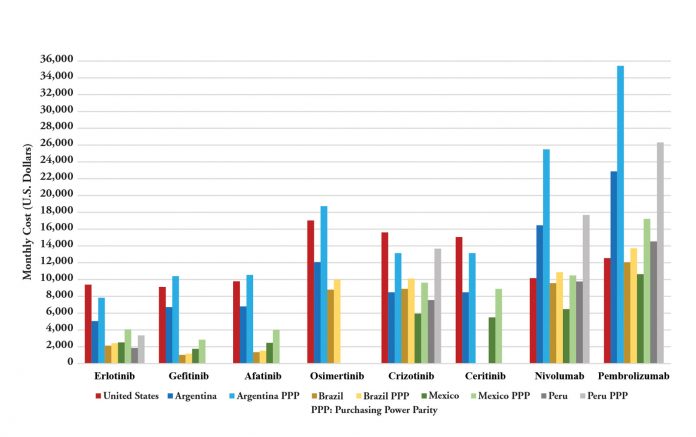

Although the United States has the highest prices worldwide, when drug costs are evaluated in relation to each country’s gross domestic product per capita,7 it becomes apparent that new cancer medications are even farther out of reach in other locations.8 Figure 1 illustrates prices for innovative lung cancer drugs in Latin America and in the United States. When adjusted by income, the cost of immune checkpoint inhibitors is higher in Latin America than in the United States. Patient selection by PD-L1 expression, and hopefully by even better biomarkers in the future, should improve cost effectiveness and decrease the budgetary effects of new drugs by limiting or curtailing use in patients who are unlikely to benefit.9 However, in the meantime, we must develop policies that can help increase access.

Barriers: Access to Care

There are also disparities within each Latin American country. In the region, healthcare provision often comes in two varieties: public health systems (funded by governments) and private services (funded mostly by employer and employee contributions). The public health system is responsible for the treatment of approximately 75% to 90% of residents, depending on the country.10

In public health systems, EGFR and ALK TKIs and immune checkpoint inhibitors are not yet widely available. In Brazil, the monthly cost of anti-EGFR TKIs is more than three times the amount hospitals and clinics receive from the government for the treatment of patients with advanced lung cancer.11 Only services with additional forms of funding (such as philanthropy or supplementation by state governments, the ministry of education, or others) are able to purchase first-generation anti-EGFR TKIs. In Panama, gefitinib is available through the National Institute of Oncology healthcare system, which treats some patients from the public health system, but patients in other healthcare systems and those without insurance have no access to EGFR TKIs.2

As a result, the proportion of patients with access to targeted therapy in Latin America is very low. Indeed, even molecular testing is done less often than it should be. A database including 11,684 patients with lung cancer treated in Brazil showed that only 13% of patients were tested in 2011, a number that improved to 58% in 2016 (mostly reflecting increased testing in the private sector, however12). Little has been published on access to new cancer medications in low- and middle income countries. A survey of Southeast Asia (which includes, among others, Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore, and Philippines), a region demographically similar to Latin America, showed that only 10% to 20% of eligible patients had access to the EGFR TKIs erlotinib and gefitinib. This contrasted to 80% in Singapore, a high-income country located in Southeast Asia.2

Barriers: Regulatory Approval Delays

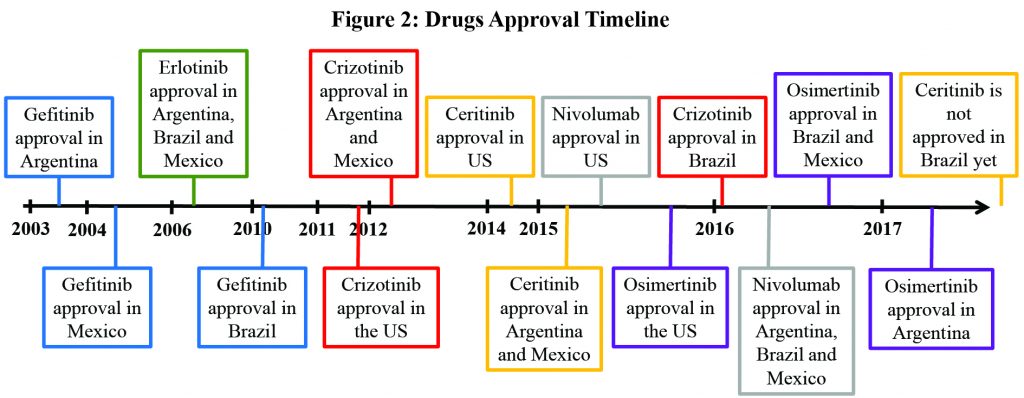

Another barrier to access are delays in regulatory approval compared to the United States. An analysis of a basket of 23 cancer drugs approved after 2002 in Brazil showed that it took ANVISA, the local agency, more than 2 years13 longer than the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to approve new medications. Osimertinib obtained approval in Mexico and Brazil in September 2016 and December 2016, respectively, approximately 1 year after the United States. Osimertinib was approved in Argentina in June 2017. A particularly egregious example, however, was the 5 extra years that it took to bring crizotinib to Brazil. It was only after calculations of life-years lost and mobilization of patient advocacy groups and the public that the drug was finally approved (and ANVISA started to accept outcomes other than overall survival in its review process). Brazil is still waiting for the approval of a second-generation ALK TKI. In Argentina and Mexico, ceritinib has been approved since 2015. (Figure 2)

Hope on the Horizon

Although it is an uphill struggle, progress is being made. Latin America has started to reform its healthcare systems to face noncommunicable diseases and cancer. Such reforms include increased training of professionals, expanded cancer registries and national cancer control plans, and the implementation of policies to improve primary prevention (especially curtailing tobacco consumption), early diagnosis, and treatment of cancer in general and of lung cancer, in particular. We hope that access to new cancer medications will also become a priority,14 and that all stakeholders—including governments, pharmaceutical companies, patients, physician organizations, and the general public— will join forces to face this challenge. ✦

About the Authors: Dr. Aguiar is a Board-Certified Clinical Oncology Physician in Brazil. He has a Masters Degree in Clinical Oncology by Universidade Federal de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil and is a PhD Fellow in the Faculdade de Medicina do ABC, Santo André, Brazil. Dr. Lopes is Medical Director for International Programs, Associate Director for Global Health, and Associate Professor of Medicine at the Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of Miami.

References:

1. Marrero SL, Bloom DE, Adashi EY. Noncommunicable diseases: a global health crisis in a new world order. JAMA. 2012;307(19):2037-2038.

2. Raez LE, Santos ES, Rolfo C, et al. Challenges in Facing the Lung Cancer Epidemic and Treating Advanced Disease in Latin America. Clin Lung Cancer. 2017;18(1):e71-e79.

3. Lung cancer in the Americas. Pan American Health Organization website. paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_download&gid=22070&itemid=&lang=en. Published 2014. Accessed January 1, 2017.

4. Lopes Gde L Jr, de Souza JA, Barrios C. Access to cancer medications in low-and middleincome countries. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2013 Jun;10(6):314-322.

5. Wilking N, Jönsson B. A pan-European comparison regarding patient access to cancer drugs. www.med.mcgill.ca/epidemiology/courses/EPIB654/Summer2010/Policy/Cancer_Report Karolinska.pdf. Accessed July 30, 2017.

6. Mailankody S, Prasad V. Five Years of Cancer Drug Approvals. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(4):539.

7. The World Bank. Purchasing Power Parities and the Real Size of World Economies – A Comprehensive Report of the 2011 International Comparison Program. 1st ed. Washington, DC: World Bank Group; 2015.

8. Goldstein DA, Clark J, Tu Y, et al. A global comparison of the cost of patented cancer drugs in relation to global differences in wealth. Oncotarget. 2017;8(42):71548-71555.

9. Aguiar PN, Perry LA, Penny-Dimri J, et al. The effect of PD-L1 testing on the cost-effectiveness and economic impact of immune checkpoint inhibitors for the second-line treatment of NSCLC. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(9):2256-2263.

10. Health Coverage Reaches 46 Million More in Latin America and the Caribbean, says new PAHO/WHO–World Bank report. The World Bank website: http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2015/06/22/health-coverage-reaches-46-million-more-in-latin-america-and-the-caribbean-says-new-paho-who-world-bank-report Published 2015. Accessed July 30, 2017.

11. Aguiar P, Roitberg F, Tadokoro H, De Mello RA, Del Giglio A, Lopes G. P2.03-006 How Many Years of Life Have We Lost in Brazil Due to the Lack of Access to Anti-EGFR TKIs in the National Public Health System? J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12(11):S2129.

12. S Palacio, G Lopes, R Mudad, E Prado. P1. 06-018 EGFR Mutations and ALK Gene Rearrangements: Changing Patterns of Molecular Testing in Brazil. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12(11):S1992.

13. Martin de Bustamante M, Martin de Bustamante M, Duttagupta S, et al. Regulatory Approval for Oncology Products In Brazil: A Comparison Between The FDA And Anvisa Approval Timelines. Value Health. 2015 Nov;18(7):A826.

14. Strasser-Weippl K, Chavarri-Guerra Y, Villarreal- Garza C, et al. Progress and remaining challenges for cancer control in Latin America and the Caribbean. Lancet Oncol. 2015 Oct;16(14):1405-1438.