By Douglas Arenberg, MD

Posted: February 2018

Posted: February 2018

There has been rapid change over the past decade in the field of lung cancer. Advances such as histology-specific treatments, targeted agents, immunotherapy, screening, and biomarkers dominate scientific journal pages, and rightfully so. Now more than ever, we lung cancer specialists have more tools to work with to reduce suffering and death from lung cancer.

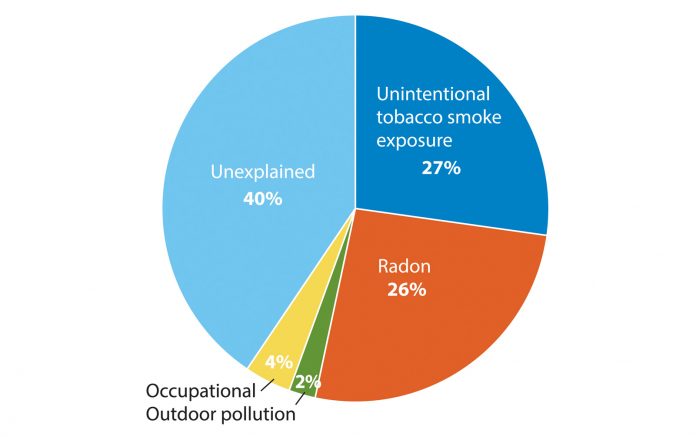

In the midst of such dizzying change, it is useful to step back and observe the big picture. A big-picture moment came for me, as an advocate for lung cancer screening, in realizing that (for my patients), I needed an increased focus on tobacco cessation and other risk-reduction tools. The goal of lung cancer screening— fewer lung cancer deaths—can be realized efficiently and with less risk by reducing exposure to known risk factors, most prominently tobacco smoke. Yet, in addition to tobacco smoke, we have irrefutable evidence from epidemiologic studies of other modifiable risk factors, specifically radon (Fig. 1). In achieving our big-picture goal, we would do well to understand all of the modifiable lung cancer risk factors and to work toward reducing them. In that regard, and in light of the fact that at the time of this article’s writing (January) it is Radon Awareness Month, let us pause to recognize and understand the role of radon, its detection, and its mitigation in reducing lung cancer mortality.

Understanding Radon and Its Relation to Lung Cancer

Radon is a natural product of the decay of uranium in the earth’s crust. It is almost universally present in the air we breathe. Although it is undetectable by the senses, it is dangerous to people living in dwellings where radon gas can accumulate. As radon decays, its daughter molecules are metals that deposit in the lung and, in turn, decay yielding both alpha and beta particle emissions that can damage DNA. On the surface, this may seem like a complex problem, but radon detection and mitigation are actually quite simple. Whereas most of what we know about radon-related lung cancer risk comes from studies of high-level occupational exposure, there is strong epidemiologic evidence that residential radon exposure contributes to lung cancer risk.1-3 Additionally, while the United States Environmental Protection Agency has set a cutoff level of 4 picocuries per liter (pCi/L) as a recommended action level,4 most radon attributable lung cancer deaths likely occur in people with exposures below this level,5 simply because of the size of the exposed population. Therefore, current recommendations from United States Center for Disease Control and Prevention are that all homeowners should check their indoor radon levels.

In any given dwelling, radon levels are highest below grade (in the basement), but levels do not necessarily diminish on higher floors, especially in newer homes with more efficient air recirculation. Consequently, radon testing should be done in the lowest level of the home, particularly if the homeowner plans to use the basement as a living space. The cost of testing kits is not very high ($15 to $30, on average), and nearly every hardware store carries these kits. Both short- and long-term tests exist, and both should be used to assess the risk of radon exposure in any given home. Cancer risk arises from long-term exposure, so a short-term test showing low radon levels cannot be considered reassuring until long-term monitoring shows low average exposure levels over a longer interval (6 months or more, with average levels ≤4 pCi/L). Homes with high radon levels can usually be easily structurally modified in a day. In the United States, most state health departments have a list of certified radon contractors. Furthermore, some states offer free testing kits. Excellent resources for physicians and consumers interested in more information can be found at epa.gov/radon.

Tobacco cessation and radon mitigation may never not off er the immediate gratifi cation of a major response to targeted agents or immunotherapy, but they are crucial to reducing the global public health risk of lung cancer and other related malignancies. ✦

About the Author: Dr. Arenberg is an Associate Professor of Medicine and Director of Lung Cancer Screening Program at University of Michigan Medical Center.

References:

1. Ruano-Ravina A, Rodriguez MC, Cerdeira- Carames S, Barros-Dios JM. Residential radon and lung cancer. Epidemiology. 2009;20(1):155- 156.

2. Thompson RE, Nelson DF, Popkin JH, Popkin Z. Case-control study of lung cancer risk from residential radon exposure in Worcester county, Massachusetts. Health Phys. 2008;94(3):228-241.

3. Wilcox HB, Al-Zoughool M, Garner MJ, et al. Case-control study of radon and lung cancer in New Jersey. Radiat Prot Dosimetry. 2008;128(2):169-179.

4. Neuberger JS, Gesell TF. Residential radon exposure and lung cancer: risk in nonsmokers. Health Physics. 2002;83(1):1-18.

5. Gray A, Read S, McGale P, Darby S. Lung cancer deaths from indoor radon and the cost effectiveness and potential of policies to reduce them. BMJ. 2009;338:a3110.