By Jyoti Malhotra, MD, MPH and Paolo Boffetta, MD, MPH

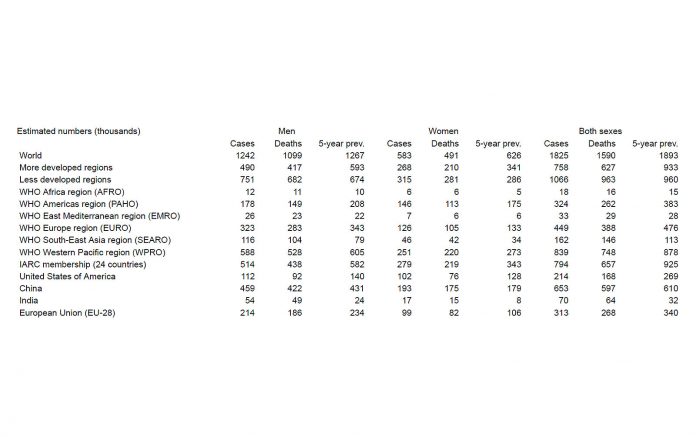

Lung cancer is the most frequent malignant neoplasm in most countries worldwide, and the main cause of cancer death in both sexes.1,2 As per GLOBOCAN, lung cancer accounted for an estimated 1,242,000 new cases among men, which is 17% of all cancers excluding non-melanoma skin cancer, and 583,000 (9%) of new cancer cases among women in 2012. Approximately 58% of all cases occur in middle and low income countries.3 Lung cancer also accounts for 19% of all cancer deaths.4 Among both women and men, the incidence of lung cancer is low in persons under age 40 and increases up to age 75 to 80 in most populations.

Based on figures from World Health Organization (WHO), age-standardized mortality rates from lung cancer (at all ages) increased in most developing countries worldwide except for Central American countries (Mexico, Panama) between 2002 and 2012. For men, overall lung cancer mortality between 2002 and 2012 decreased in several countries worldwide.5,6 Thus, the declines in lung cancer mortality rates in men have continued over recent years, and are projected to persist for the near future.7 Overall female lung cancer mortality has been lower than in men, but has been increasing up to the recent years in most countries.

Trends in lung cancer mortality can be interpreted in terms of different patterns of smoking prevalence in subsequent cohorts of people in various countries,8,9 as tobacco smoking remains the major cause of all major histologic types of lung cancer in developing countries as well. An increase in tobacco consumption is paralleled a few decades later by an increase in the incidence of lung cancer. Similarly, the temporal lag in trends in female and male lung cancer mortality reflects historical differences in cigarette smoking between subsequent female and male cohorts.10,11 The higher rate of lung cancer among African Americans as compared to other ethnic groups in the United States is probably explained by their higher tobacco consumption.12 The lower risk of lung cancer among smokers in China and Japan as compared to Europe and North America might be due to relatively recent introduction of regular heavy smoking in Asia, although differences in the composition of traditional smoking products and in genetic susceptibility might also play a role.13 The importance of tobacco smoking in the causation of lung cancer complicates the investigation of the other causes, because tobacco smoking may act as a powerful confounder or modifier. Although cigarettes are the main tobacco product smoked in western countries, an increased risk of lung cancer has also been shown following consumption of local tobacco products, such as bidi and hookah in India and khii yoo in Thailand, and the use of water pipes in China.14

Chronic inflammation seen with infections more prevalent in developing countries may also play a role in lung carcinogenesis. Patients with pulmonary tuberculosis have been found to be at increased risk of lung cancer.15 In the most informative study, involving a large cohort of tuberculosis patients from Shanghai, China,16 the risk of lung cancer exceeded twofold in the subjects with a history of tuberculosis within the last 20 years. Six studies exploring risk of lung cancer among individuals with markers of Chlamydia pneumoniae infection have also consistently detected a positive association.17 Other notable risk factors for lung cancer in developing countries include indoor air pollution and occupational exposures. Indoor air pollution is especially a major risk factor for lung cancer in never-smoking women living in several regions of Asia. This includes coal burning in poorly ventilated houses, burning of wood and other solid fuels, as well as fumes from high-temperature cooking using unrefined vegetable oils such as rapeseed oil.18 In many low- and medium-resource countries, occupational exposure remains widespread, with the most important occupational lung carcinogens reported to be asbestos, silica, radon, heavy metals, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs).19,20

For lung cancer prevention worldwide, control of tobacco smoking is the most important preventive measure. Other priorities for the prevention of lung cancer include control of occupational exposures as well as indoor and outdoor air pollution, and understanding the carcinogenic and preventive effects of other lifestyle factors. ✦

References

1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin 2015: 65(1): 5-29. Epidemiology of Lung Cancer in Developing Countries By Jyoti Malhotra, MD, MPH and Paolo Boffetta, MD, MPH P E R S P E C T I V E Jyoti Malhotra Paolo Boffetta

2. Malvezzi M, Carioli G, Bertuccio P, Rosso T, Boffetta P, Levi F, La Vecchia C, Negri E. European cancer mortality predictions for the year 2016 with focus on leukemias. Ann Oncol 2016.

3. Foreman D, Bray F, Steliarova-Founcher E, Ferlay J, Brewster D. Cancer Incidence in Five Continents IARC Scientiĺc Publication 1o 164 Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer 2014: X.

4. Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer 2015: 136(5): E359-386.

5. World Health Organization Statistical Information System. WHO mortality database. Available at: http://www3.who.int/whosis/menu.cfm/ [last accessed: December 2015].

6. Malhotra J, Malvezzi M, Negri E, La Vecchia C, Boffetta P. Risk factors for lung cancer worldwide. Eur Respir J 2016.

7. Malvezzi M, Bosetti C, Rosso T, Bertuccio P, Chatenoud L, Levi F, Romano C, Negri E, La Vecchia C. Lung cancer mortality in European men: trends and predictions. Lung Cancer 2013: 80(2): 138-145.

8. Graham H. Smoking prevalence among women in the European community 1950-1990. Soc Sci Med 1996: 43(2): 243-254.

9. Franceschi S, Naett C. Trends in smoking in Europe. Eur J Cancer Prev 1995: 4(4): 271-284.

10. Thun M, Peto R, Boreham J, Lopez AD. Stages of the cigarette epidemic on entering its second century. Tob Control 2012: 21(2): 96-101.

11. Malvezzi M, Bertuccio P, Levi F, La Vecchia C, Negri E. European cancer mortality predictions for the year 2012. Ann Oncol 2012: 23(4): 1044-1052.

12. Devesa SS, Grauman DJ, Blot WJ, Fraumeni JF. Cancer surveillance series: changing geographic patterns of lung cancer mortality in the United States, 1950 through 1994. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 1999: 91(12): 1040-1050.

13. Yuan J-M, Koh W-P, Murphy SE, Fan Y, Wang R, Carmella SG, Han S, Wickham K, Gao Y-T, Mimi CY. Urinary levels of tobacco-specific nitrosamine metabolites in relation to lung cancer development in two prospective cohorts of cigarette smokers. Cancer research 2009: 69(7): 2990-2995. 14. World Health Organization IAfRoC. Tobacco smoke. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans Vol 83 Tobacco Smoke and Involuntary Smoking. Lyon, France, Lyon, France, 2004; pp. 51–1187.

15. Aoki K. Excess incidence of lung cancer among pulmonary tuberculosis patients. Japanese journal of clinical oncology 1993: 23(4): 205-220.

16. Zheng W, Blot W, Liao M, Wang Z, Levin L, Zhao J, Fraumeni Jr J, Gao Y. Lung cancer and prior tuberculosis infection in Shanghai. British journal of cancer 1987: 56(4): 501.

17. Littman AJ, Jackson LA, Vaughan TL. Chlamydia pneumoniae and lung cancer: epidemiologic evidence. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention 2005: 14(4): 773-778.

18. International Agency for Research on Cancer WHO. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Vol. 95. Household use of solid fuels and high-temperature frying. IARC, Lyon, France, 2006.

19. Cogliano VJ, Baan R, Straif K, Grosse Y, Lauby- Secretan B, El Ghissassi F, Bouvard V, Benbrahim- Tallaa L, Guha N, Freeman C, Galichet L, Wild CP. Preventable exposures associated with human cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst 2011: 103(24): 1827-1839. 20. Humans IWGotEoCRt. Chemical agents and related occupations. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum 2012: 100(Pt F): 9-562.