Tobacco smoking dramatically increases the risk of developing lung cancers, and it has long been recognized that nicotine addiction is one of the biggest obstacles to changing current smokers’ behavior. IASLC Lung Cancer News recently spoke with Laura Jean Bierut, MD, Professor of Psychiatry, from the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Missouri, about the link between smoking and genetics, the success of current anti-smoking policies, and how e-cigarettes might impact smoking in the coming years.

Q: Is there a heritable, genetic component to either tobacco addiction or lung cancer?

A: Yes, there is no doubt that genetic variation in the population affects both smoking behaviors and the development of lung cancer. Genetic studies have identified variants with the strongest influence on the risk of developing lung cancer or COPD in a region of Chromosome 15, and these are precisely the same variants that have been identified as influencing smoking behaviors. The variant that we know the most about is a single nucleotide polymorphism called “rs16969968,” and it causes an amino acid change in the alpha-5 nicotinic receptor [CHRNA5]. This variant actually alters the conductance of the receptor in the cell, which is an elegant real-world demonstration of pharmacogenetics. There are other genetic risk variants in other regions of the genome, too, and all of these fall in chromosomal regions containing nicotinic receptors and enzymes involved in nicotine metabolism.

Q: Does the rs16969968 variant have any implications for smoking prevention or cessation strategies?

A: This variant plays essentially no role in whether an individual initiates smoking or not, which is strongly driven by environmental factors. However, if a person with the high-risk allele does begin smoking, they will smoke a higher number of cigarettes per day, have a higher intensity of smoking, and have a higher age of smoking cessation than those with the low-risk variant, increasing their risk for lung cancer. The problem with smoking cessation pharmacotherapy using nicotine replacement therapy is that it works modestly, at best, and the vast majority of smoking cessation is done without any medication. However, data suggest that people with the high-risk variant rs16969968 have the greatest difficulty quitting and stand to benefit the most from medication, although the evidence is still controversial. This makes sense since this variant affects nicotine receptor function. Improved implementation of pharmacotherapy, using patients’ genetics as a guide, could have a huge public health impact.

Q: What other interventions, aside from smoking cessation programs, work best for preventing or curtailing tobacco addiction?

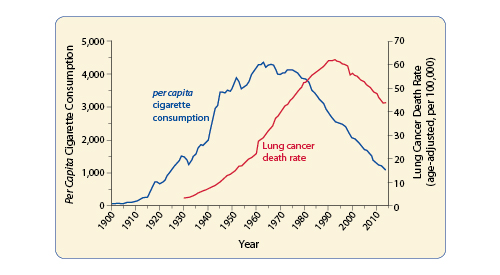

A: Policies like age restrictions for purchasing tobacco, increased taxation, and indoor smoking bans have made a tremendous impact already. Even in places where taxation and clean air policies have not decreased overall smoking rates, they have reduced the amount of cigarettes people smoke because of the increased cost of tobacco products and the decreased opportunities to smoke during the day. This is one of the great public health successes in the US. If you plot per capita cigarette consumption in the US and lung cancer rates on the same graph, you can see the clear relationship between declining smoking rates and reduced incidence of cancer (Figure 1). Internationally, the US has historically been at the forefront of tougher antismoking legislation, and the public health benefits have been observed here first. Europe has implemented similar policies and is catching up in terms of reduced smoking rates and cancer incidence, if they have not already overtaken us. China is on the other end of the spectrum. It has a state-owned tobacco industry, which has hindered the implementation of antismoking public policies, so smoking rates remain high, and the incidence of tobacco-related cancers is on the rise.

Q: Over the last several years, new smoking substitutes have been introduced to the market like electronic cigarettes [also known as e-cigarettes or electronic nicotine delivery systems]. How will these technologies affect the rates of smoking and lung cancer going forward?

A: E-cigarettes have only been out for about 10 years, so we don’t know the answer to this question yet. It is a fact that combustible cigarette smoking is at its lowest rate ever among high school students, which is great. However, the rate of e-cigarette use is increasing among this same age group and has already surpassed that of combustible cigarette use. While the health risks of e-cigarettes are far less than those of combustible cigarettes, we cannot say that they are risk-free. The critical issue is whether or not those using e-cigarettes now will eventually